Even if they’d never made a single Scrappy cartoon at 861 Seward St. in Los Angeles, the address would have its place in animation history. After all, it was home to the Harman-Ising studio. And Bambi sprung from work done there. And the Walter Lantz studio was headquartered in the building for many years.

And partway through all of that, Screen Gems–the former Charles Mintz studio–was located at 861 Seward. Columbia moved the operation there in 1940–leaving behind 7000 Santa Monica Blvd.–after Charles Mintz’s death at the end of 1939. It’s therefore the last location I have to cover in this series on Scrappy’s homes, which began with my piece on 1154 N. Western Ave.

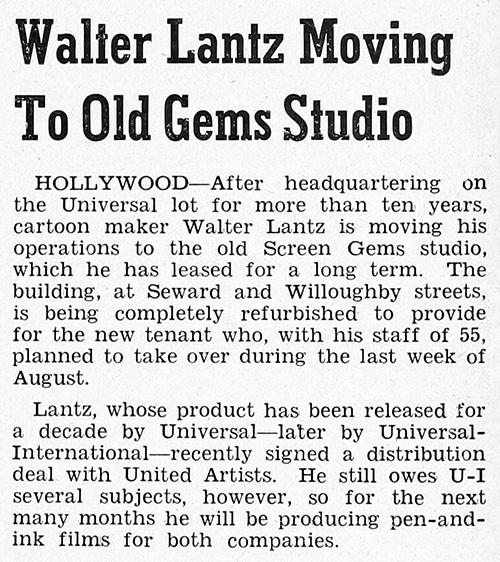

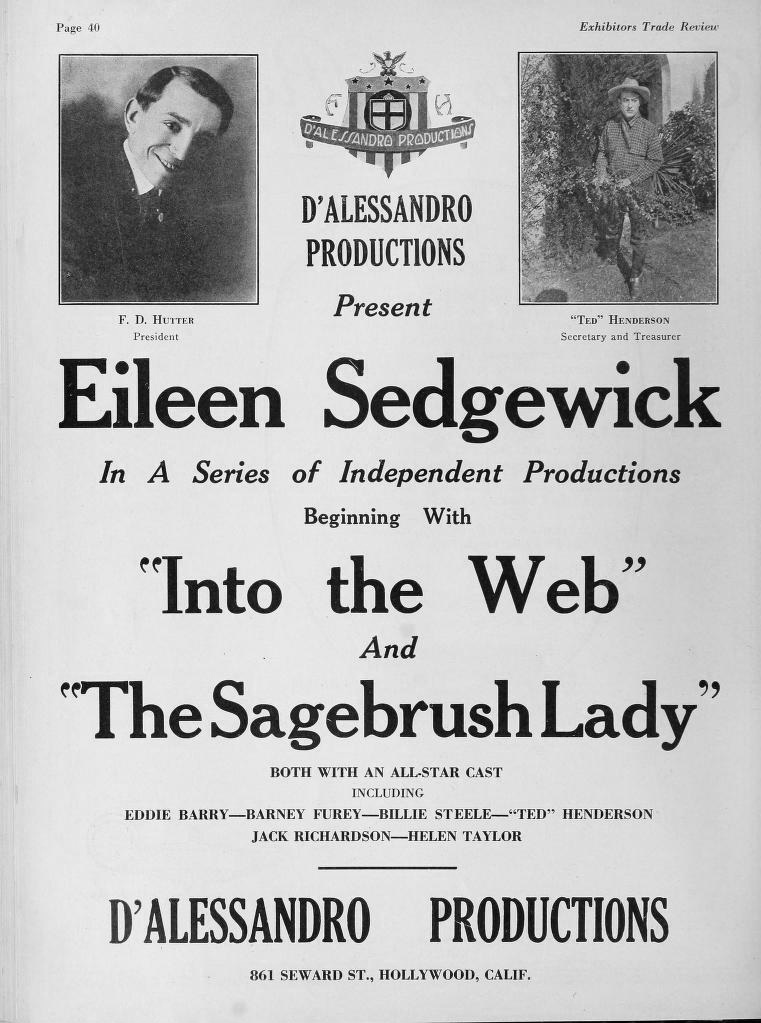

861 Seward St. was built in 1924 and was apparently devoted to the making of movies from the start. The earliest mention of it I’ve found in trade journals is from that December. Here’s that reference, in an ad for D’Alessandro Productions, producer of The Sagebrush Lady.

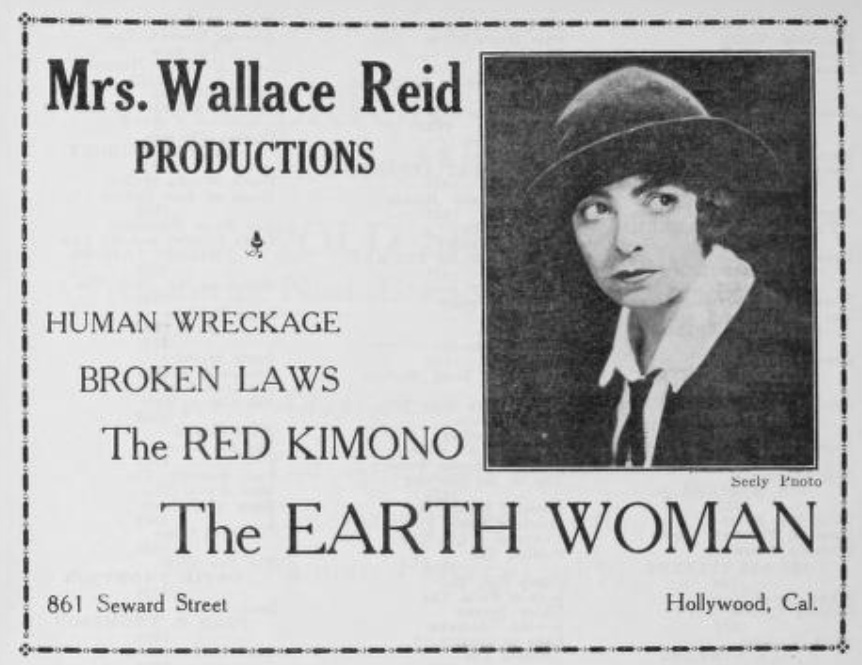

Other companies in the building during the same era included Walter W. Kofeldt Inc., a film importer; and the wonderfully-named Mrs. Wallace Reid Productions, which an actress named Dorothy Davenport named to leverage the brand power of her late husband, a silent star who had died in a sanitarium where he was attempting recovery from his morphine addiction. (Human Wreckage, mentioned in the ad below, had an anti-drug message.)

In Hollywood Cartoons, Mike Barrier cites Rudolf Ising as remembering that Disney used a laboratory at 861 Seward for film processing in the 1920s; Martha Sigall’s Living Life Inside the Lines is more specific, saying that Steamboat Willie had been developed there. And indeed, a lab called National Aeromap that catered to the movie industry was in the building by 1926 and stayed there for at least a few years. Seward St. may have been a bit of a film-processing district: The 1932 Film Daily Yearbook lists five lab facilities on the street, including one belonging to Technicolor.

The June 25, 1935 Film Daily reported that the Harman-Ising studio–by now making shorts for release by MGM–was moving into 861 Seward to get the space it needed to make more cartoons and adopt three-strip Technicolor. (The two-reelers referenced below–one of which might have been based on “The Nutcracker”–did not get made.)

In February of 1937, MGM terminated its contract with Harman-Ising. The two animators worked on other projects such as Merbabies–which Disney released as a Silly Symphony–but went bankrupt. They then joined a new MGM cartoon studio, overseen by Fred Quimby and located on the studio lot.

This website may be about Scrappy cartoons, but let’s be honest: 861 Seward’s next era was its most intriguing. Disney, which was in the process of building its new Burbank studio, was out of room at its old Hyperion one and had to shunt some projects into other premises. It leased Harman-Ising’s Seward St. space and moved the group doing early work on Bambi into the building in October 1938.

It wasn’t until I began thinking about 861 Seward’s Screen Gems years that I realized I’d talked about its Disney period with Maurice Noble in 1991, when he told me about his work on Bambi:

About that time [Disney] were constructing their new studio in Burbank, and the Bambi unit was shifted over to a small building down in Hollywood on Seward Street. That’s where we were isolated for almost two years. All I did on that particular picture was sketchwork; I probably did three or four thousand watercolor sketches for it. As it finally appeared, my influence was probably minimal, because they decided to go with the approach that Tyrus Wong gave it – a certain Oriental flavor, if you recall the film. My view of the story of Bambi was more on the grand scale, and Tyrus’s rendering and type of background seemed to lend itself to the intimate approach. My contributions were probably more indirect on the film.

Mike Barrier’s Hollywood Cartoons says that Walt Disney himself rarely showed up at Seward St. In Walt Disney’s Bambi: The Story and the Film, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston make the outpost sound rather pleasant:

At first there was much resentment over on Seward at being separated from the stimulation of the main studio, but gradually the staff realized that there were certain benefits in being isolated. Clair Weeks, artist and story sketch man, said, “It was … sort of a little paradise we had … free of the hurly-burly of Hyperion–nobody bothered us.” No one made trips back to the main studio and the only person who came over to Seward was Mr. Keener, the paymaster.

In the fall of 1939, Disney’s Seward St. lease ran out and the Bambi unit moved to the new Burbank studio. Screen Gems moved in the following year. I don’t know what instigated the relocation from Santa Monica Blvd. but perhaps it had something to do with Columbia’s consolidation of control over the studio.

By that time, the Scrappy series was withering away. Paul Etcheverry and Will Friedwald’s Scrappy filmography lists only seven shorts released in 1940. None of them were classics and some were Scrappy cartoons in only a technical sense at best.

The final Scrappy, The Little Theatre, was released in February 1941. 861 Seward, in other words, was the place where Scrappy died.

If you’re interested enough in old cartoons to be reading this website, you probably know what happened at Screen Gems as the ’40s wore on. The last vestiges of the Mintz years gave way to an era of revolving-door management (including Frank Tashlin and Dave Fleischer, among others); a failure to create new successful new series (with the Fox and Crow cartoons as the closest thing the studio had to a flagship); and an approach that veered from experimental to generic and then back again without giving Disney, Warner, or MGM any reason to worry. Hollywood business directories show Screen Gems as being located at 861 Seward through 1946. As far as I know, it was there until Columbia ceased producing its own cartoons.

I don’t have any fascinating facts about the studio’s time there. Well, maybe one: When I visited the building, I saw that it was at the intersection of Seward and Willoughby:

And it dawned on me that Willoughby Ave. must have provided the Screen Gems character Willoughby Wren, a tiny strongman, with his name. I already dimly knew that the Lantz studio named Inspector Willoughby (whose first name is Seward) after its intersection; Willoughby Ave. must be the only street in Hollywood to have inspired two cartoon characters.

Here’s Willoughby Wren in Bob Wickersham’s Magic Strength:

861 Seward wasn’t bereft of animation activity for long. In August 1947, Box Office reported that the Walter Lantz studio, which was severing its ties with Universal (temporarily, it turned out), had leased the place.

The best thing about Lantz’s long residency at 861 Seward—at least from a Scrappyland perspective—is that we have film footage documenting it. The early years of TV’s Woody Woodpecker Show featured numerous mini-documentaries about the making of cartoons, with Lantz employees coming up with stories, animating them, painting cels, and running animation cameras. Judging from the scenes that made it onto TV, it wasn’t the world’s most evocative Hollywood animation studio, but I’m glad this material survives. Here’s some of it.

At least one animation notable, Sid Marcus, worked for both Screen Gems and Lantz in their respective 861 Seward eras; I’ll bet there were other folks who did, too. If you can identify any of the faces in the video above, please let me know. (And if Lantz shot these live-action segments at a soundstage elsewhere in Hollywood, don’t tell me.)

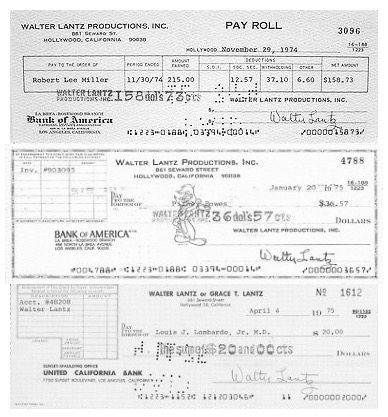

Another neat thing about 861 Seward’s Lantz years: If you want a memento of them, you can go on eBay and buy any one of a surprisingly large number of checks signed by Walter Lantz and bearing that address.

Walter Lantz seems to have bought his building at some point, which I imagine was a savvy investment. As his studio’s production slowed, he began renting out space to other companies. According to Martha Sigall’s Living Life Inside the Lines, one such tenant was the commercial studio operated by the great Warner Bros. animator Abe Levitow. And here’s a letter–which I borrowed from ChipJacobs.com–in which Lantz agrees to least space “formerly occupied by an [sic] our animators” to Gordon Zahler’s General Music Company. (Jacobs is the author of Strange as It Seems, a biography of Zahler–who was, among other things, Lantz’s partner in the Walter Lantz Music Company, a purveyor of stock music for other cartoon studios, and the man who patched together a score for Ed Wood’s Plan 9 From Outer Space.)

Even after Lantz ceased production of cartoons in 1972, it retained offices at 861 Seward. It remained there until at least the late 1970s, but eventually moved less than half a mile to 6311 Romaine, an art deco building known as Television Center that had once been the original Technicolor film-processing laboratory.

After Lantz moved out of 861 Seward, the building was home to a variety of small, obscure Hollywood-type outfits: Schulman Video Services and JPJ Productions were two of them. Eventually, it housed a post-production company called Laser-Pacific–which was successful enough that it was bought by Technicolor in 2011. Today, that company continues to provide services to Hollywood out of 861 Seward. (I was too shy to go in when I dropped by in 2017, but maybe I’ll try to arrange a tour someday.)

To recap: Walter Lantz ended up moving into Technicolor’s former headquarters, and Technicolor ended up taking over Walter Lantz’s former headquarters. That’s surely evidence that Hollywood is a small town. And given that the Screen Gems brand still exists–as a label for Sony horror films and an independent operator of film production facilities–it isn’t entirely unthinkable that the current incarnation of the studio that gave us Scrappy could return to its one-time home a mere eight decades after it first moved in.

I work about a couple of blocks from this famous old building, and it’s an amazing neighborhood with a lot of Hollywood history: Todd-AO Sound was just half a block from Lantz’ office and is now a bustling state-of-the-art Deluxe color theater. And the Television Center mentioned in the article was the original 1915 home of Technicolor all the way until about 1960. The ghost of Natalie Kalmus still roams the halls late at night…

Thanks, Marc. If you’re still doing the kind of stuff you did when we were in Apatoons together, I’m not surprised you work in this neighborhood.

I’m out of Mintz studios to write about (unless I go back and write about where they were in New York) but almost want to go on writing about the histories of long-standing buildings in Hollywood—it’s fun!

The animation story of 861 runs even deeper. In May of 1933, pioneer, J. Stuart Blackton had his office at 861 Seward.

Great factoid—thanks, Joe!

I read somewhere that Gloria Estefan had bought the Walter Lantz building at one point and planned to remodel it into a recording studio. Whether she followed through on this, I don’t know. It probably would have been shortly before Laser Pacific occupied the space.

As of 2022, It seems that Technicolor has moved out, and a new company, Formosa Group/Streamland Media, has moved in. Apparently they specialize in Post-Production and VFX Services.