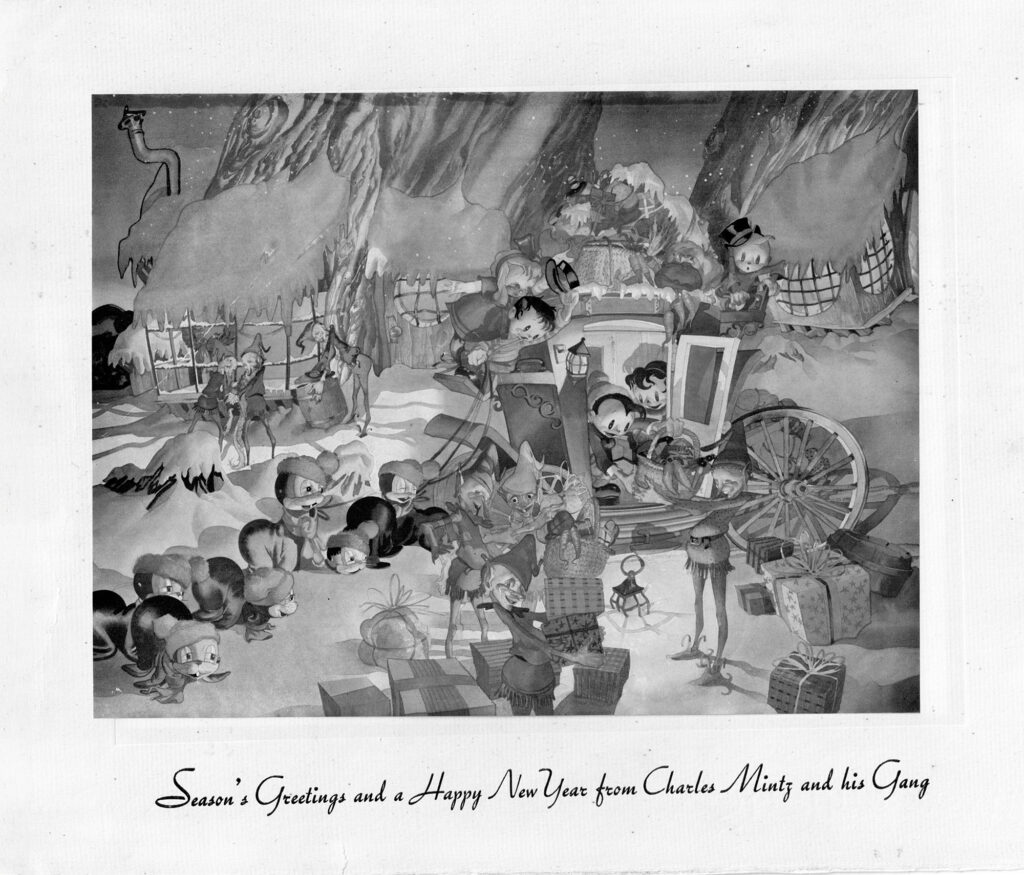

Here’s a recent addition to the Scrappyland archive, and a pretty remarkable one: a print that Charles Mintz presumably sent out to personal friends and/or business associates in the mid-to-late 1930s. I know it looks like a Christmas card, but it’s much larger than one and extremely suitable for framing. If you click on it, you can inspect it at a much larger size. If you insist, you can also see a color version here.

Exactly what it depicts remains enigmatic to me. The lad inside the wagon is surely Scrappy, and the girl with him looks like a brunette version of Margy. The boy doffing his hat on top of the wagon could be Scrappy, though he might just be a generic 1930s cartoon kid of the sort who appeared in Mintz’s Color Rhapsodies. That would mean the girl next to him is likely not Margy herself but simply Margyesque. But that must be Oopy on the other end of the wagon roof. Right?

The wagon is being pulled—or, actually, not pulled—by what seem to be inebriated seals. Thank you to Friend of Scrappy John Vincent for pointing out their resemblance to the title character of the 1936 Screen Gems cartoon The Untrained Seal.

There are also seven spindly elves. Wrapped gifts abound—some possibly to be delivered by the kids—raising the possibility that the structures in the background are Santa’s workshop. Not present: Krazy Kat, Mintz’s other principal continuing character besides Scrappy.

I am, of course, curious who painted this idiosyncratic and opulent piece. Rather than looking like a scene from a Mintz cartoon, it has the feel of a European children’s book illustration. That turned my mind to the work of such celebrated 1930s Disney inspiration artists as Albert Hurter, Gustav Tenggren, and Ferdinand Horvath. And what do you know: Horvath worked for Charles Mintz. According to Didier Ghez’s fine 2015 book They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Golden Age, he joined the studio on May 31, 1938, after two tours of duty at Disney. “By the new year, however, he was out of work again,” Ghez writes.

I don’t know which Columbia cartoons Horvath worked on, or why his stint was so short, but his employment at the studio is an intriguing glimmer of ambition on Mintz’s part. After leaving Columbia and failing to get re-rehired at Disney, the artist briefly sculpted characters for George Pal’s Puppetoons. Then he tried again at Disney. When that didn’t pan out, he left animation.

Horvath, who famously contributed pre-production art to Snow White, certainly had a quaint style in the same aesthetic Zip Code as Charlie Mintz’s Christmas print. But after studying examples of his drawings from Ghez’s book and elsewhere, I haven’t found any that obviously identify him as our mystery artist. Indeed, I’m inclined to say he probably wasn’t. Maybe someone else at the studio was also capable of this fairy tale-esque flair: If you know of any candidates, I’d love to hear about them.

Season’s greetings and a happy new year to you from me and the entire Scrappyland gang.